So in spite of the very special new kind of pandemonium that Little Miss has introduced to our lives, I managed to read this latest adventure in the world of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials in just three days. This is not a brag about my reading speed but a measure of just how readable La Belle Sauvage is. If a book is so exciting that you, sleep-deprived and exhausted new Mum, are prepared to stay awake AFTER your three month old has gone to sleep in order to read it, I think it’s fair to say you’re onto something pretty special.

So in spite of the very special new kind of pandemonium that Little Miss has introduced to our lives, I managed to read this latest adventure in the world of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials in just three days. This is not a brag about my reading speed but a measure of just how readable La Belle Sauvage is. If a book is so exciting that you, sleep-deprived and exhausted new Mum, are prepared to stay awake AFTER your three month old has gone to sleep in order to read it, I think it’s fair to say you’re onto something pretty special.

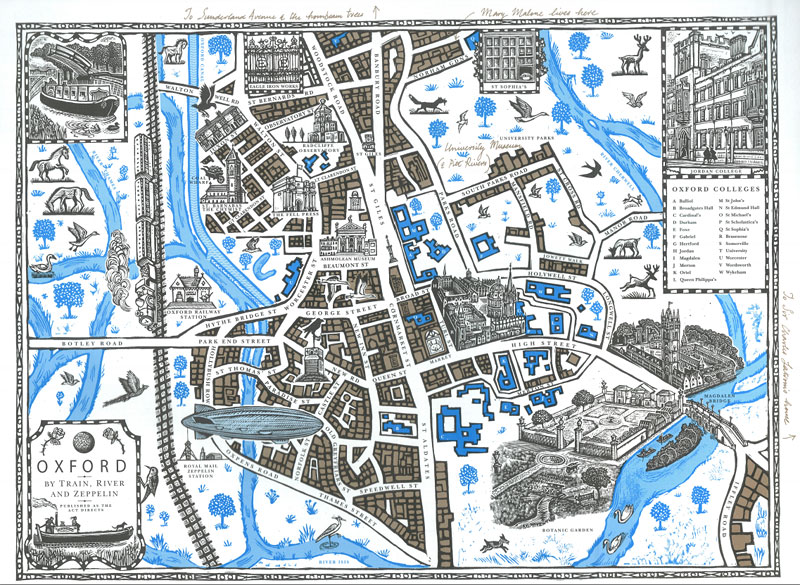

I was nervous about this read. I loved the original trilogy (so much so that Little Miss was very nearly Little Miss Lyra) and I couldn’t quite conceive of how Pullman was going to introduce new characters to Lyra’s Oxford capable of commanding the same affection (or indeed fear) as those we met in Northern Lights (The Golden Compass in the States). This nervousness was perhaps a mark of not having read any Pullman for an awfully long time. The opening pages slip you gently back into this world of daemons and Dust that you never realised you had forgotten. It’s not quite like putting on a pair of comfortable slippers – it’s a darn sight more exciting for a start – but it is reassuringly familiar.

The heroes of this tale Malcolm Polstead and Alice Parslow, residents and employees of The Trout Inn, offer gentle foreshadowings of Lyra (introduced as a baby in this book) and Will. There are guest appearances from other characters we already know too: Lord Asriel, Mrs Coulter and Father Coram pop up without any hint of that slavishness that can afflict fictional worlds revisited. Pullman draws new detail onto these characters rather than just thickening their outline. Similarly, we learn more about that mystical instrument, the alethiometer and are given insight into the conflicts and politics concerning Dust.

The tone of the book is definitely more adult than the previous trilogy (see here for much predictable bleating over the swearing) and whilst that certainly helps it to appeal to his original child’s audience now in their twenties and thirties it also adds depth and seriousness to what could otherwise have been an entertaining kids’ caper. And that, of course, is what Pullman is so good at, telling stories that are accessible, exciting and adventurous against a backdrop of complex and provocative ideas. The original His Dark Materials trilogy was rich in philosophy and it is a point of great admiration for me that Pullman refuses to patronise his younger readers.

Religion, as you would expect, is a central concern and we encounter both its kindness and abominable cruelty in two very different sets of nuns as well as the sinister reach and power of the religious authority, The Magisterium and its enforcement arm, the Consistorial Court of Discipline. The action is driven by a flood of Biblical scale and consequence sweeping our heroes away from Oxford and through various other-worlds. The pages preceding the flood are saturated with dread as they are with rain and the climactic moment that the river bursts its banks is devastating.

It isn’t just the swearing that makes La Belle Sauvage a more adult read than its forebears. Its villain, Bonneville, is genuinely scary and his Hyena daemon an exercise in the grotesque. The coming of age aspect of His Dark Materials is revisited and disturbingly played out in this character’s pursuit of Malcolm, Alice and of course the baby Lyra. Sexual assault and abuse are explicitly touched upon and the supposed moral authority of those who oppose the Magisterium called into question in their willingness to exploit children in pursuit of their agenda.

The movement of the story does lose urgency towards the end and, as one might expect, we are left with an armful of questions and very few answers. Among other things, I can’t help but wonder how Pullman will square the notable absence of Malcolm and Alice from Lyra’s life in the originals with the fierceness of protection they showed her here. That said, if there is one thing I should have learnt from La Belle Sauvage it is to trust Philip Pullman and look forward to the next instalment with new confidence that it is likely to be just as magical and mysterious.

Brief side note: I have actually leant my copy to my sister and so can’t offer any pictures at the moment (will update soon!) but beneath the dustcover, the book itself is absolutely beautiful, embossed with copper flecks of dust itself.

This year I have set myself the challenge of reading

This year I have set myself the challenge of reading